N° 87 - Tropical Abstraction

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

N° 87 - Tropical Abstraction

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

10 June - 21 August 2005

Guest curator: Roos Gortzak

Tropical

And now, what do we see? Bourgeois, sub-intellectuals, cretins of every kind, preaching ‘Tropicalism’, Tropic·lia (it’s become fashionable) – in short, transforming into an object of consumption something which they clearly cannot quite identify. It is completely clear! Those who made ‘stars and stripes’ are now making their parrots, banana trees, or are interested in slums, samba schools, outlaw anti-heroes. Very well, but do not forget that there are elements here that this bourgeois voracity will never be able to consume: the direct life-experience element, which goes beyond the problem of the image.

The above quotation comes from the artist Hèlio Oiticica (1937-1980), who in 1968 expressed his doubts about a new artistic trend in his article Tropic·lia. ‘Tropicalism’ borrowed tropical elements in a superficial manner, without taking into account the difficulty of representing a culture. This problem of representation is central to Tropical Abstraction. The works in the exhibition are concerned with the translation of something as abstract as a culture or a place into words or images, in the knowledge that many different translations are possible. Tropical Abstraction thus seeks to avoid the trap of selecting works that are superficially ‘tropical’, supposedly culturally different.

An important factor here is the distinction made by the critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha between ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘cultural difference’. Cultural diversity, according to Bhabha, acknowledges a range of separate norms and values, but maintains a colonialist prejudice that these differences are aberrant or exotic. Conversely, there is no question of a standard, established yardstick by which to measure cultural difference. Bhabha believes in the existence of ‘the space of hybridity’, in which cultural meanings and identities always contain the traces of other meanings and identities. Tropical Abstraction provides space in which old and new meanings can be examined and formulated.

Abstraction

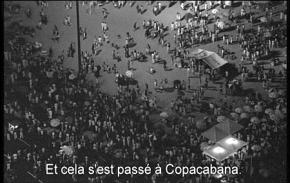

“Copacabana does not exist”, concludes a man seeking to capture in words the Brazilian beach of Rio de Janeiro. He thus places his first attempts to describe this place – Copacabana as embodiment of poetic decadence, as a universal oasis, as the only place in which Utopia could exist – in the realm of fiction. This is the ending selected that the artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster selected for her film Plages (2001); her conclusion raises the question of whether it is in fact possible to represent a place.

In her efforts to establish what constitutes a place, Gonzalez-Foerster has various people talk about their memories of Copacabana in Plages. She uses the stories as a voiceover in her unconventional portrait of this beach, filmed on a New Year’s Eve when it was packed with people, and shot from a high vantage point. The discrepancy between word and image means that Gonzalez-Foerster does not force her film version of Copacabana onto the viewer. Looking at the throngs of beachgoers, the viewer realises that every single individual has their own experience of this place and that there may be as many Copacabana beaches (the plural of the title) as there are people – and that even an individual’s memories can change from moment to moment.

Where Gonzalez-Foerster avoids the clichéd image of a tropical location in Plages, she sometimes consciously invokes it in non-tropical locations. Armando Andrade Tudela uses a similar strategy in his slideshow Diaporama and Infrared Light (2005). He casts an infrared light on his set of slides of different sites such as a desolate-looking greenhouse in Liëge and an indefinable architectonic space in the French town of St. Etienne. These are places in which he sees something of the tropics, abandoned as they seem to be to an organic process of change. The red light sheds an almost narcotic haze over the different locations, blurring their contours. He as it were detaches the greenhouse and the architectonic space from their ‘true’ location, transferring them into the more speculative realm of the imagination.

Another geographical dislocation appears in his work Sculpture Fragments (2005). His starting point was an anonymous Modernist sculpture that he encountered in the north of Peru, placed there some 35 years earlier as a monument to the nearby ruins of the pre-Inca civilisation of Chankillo. Andrade Tudela wondered to what extent this sculpture, with its geometric, abstract cube forms, could be an appropriate representation of a pre-Inca civilisation. His doubts about using such a homogenous, closed shape to reconstruct something so complex inspired him to create his own version of the sculpture. In his mind’s eye, he deconstructed the colossal, concrete original block by block, subsequently recreating the constituent parts (out of Multiplex) on the same scale. They are scattered throughout the exhibition area, mirroring the way in which the archaeological remnants of Chankillo are seen. The appearance of the original sculpture cannot be made out. It could take one of many forms, depending on how viewers reconstruct the fragments in their own imagination.

In the series of drawings entitled Fanal (2000), Fernando Bryce reinterprets not a sculpture, but a periodical. He looks back at how the 1965 Esso Prize for Peruvian artists was portrayed in a contemporary issue of the cultural magazine Fanal, published by the International Petroleum Company. He has copied all the photographs of the prize-winning works of art, the artists who received awards and the pomp and circumstance of the award ceremony - complete with captions. Recast in the ink of his handwriting, it is no longer possible to identify the original source material (glossy magazine, broadsheet or brochure). Viewers can thus look critically at the images without being burdened by prior conceptions. The knowledge that copying is a laborious and lengthy procedure also makes one aware of the way in which the awards were originally portrayed, and makes one wonder about the Petroleum Company’s underlying motives. Rather than paying tribute to the winners, Bryce’s Fanal can be seen as a criticism of Peruvian notions of Modernism in the 1960s. It is as if he places viewers in the position of the jury members, forcing them to take a critical look at the award-winning abstract sculptures and paintings.

Mariana Castillo Deball’s work is informed by a comparable interest in questioning the way in which facts are constructed, history written and culture represented. For Tropical Abstraction she produced a series of photographs of Mexican cultural icons intended to endorse the past. She is interested in the ephemeral nature and mutability of the icons selected for such endorsement. Something that is readily identifiable today may in a few years time be just as incomprehensible as an archaeological fragment from prehistory. In order to highlight the question of these icons’ sell-by-date, she combines her series of photos with a piÒata. Made of cardboard, piÒatas are usually attached to ceilings at Mexican parties and struck with sticks until they break and rain down the sweets and presents hidden within them.

An object whose sell-by-date expired some 30 years ago was chosen by Jes·s Bubu Negrûn for his project Igualdad (2004). He decided to breathe new life into the village Aòasco, whose inhabitants originally worked in one of Puerto Rico’s many sugar factories, back in the days when it still had a flourishing sugar trade. For seven days he and the villagers worked 24 hours a day to bring smoke back to the factory chimneys. Not in an attempt to produce sugar, but to bring a new visibility to a community which had become totally impoverished following the closure of the factories. This collective project restored the locals’ belief in their ability to achieve. They continue to organise festivals and musical evenings, and have set up their own website.4

Central to the Allora & Calzadilla film Under Discussion (2005) are questions that preoccupy another Puerto Rican community, the inhabitants of the little island of Vieques. It is the third work in a series about the island, which until recently was used by the American army as a bombing target. Under Discussion shows the son of a fisherman who was in the ‘civil disobedience’ movement in the 1970s, negotiating the territorial waters in a boat made of an upturned conference table. The camera follows him on his boat trip, and also looks at places on the island where traces of the Americans’ stay are still visible, together with hints of its future destiny. Past, present and future merge in this beautiful, poetic film and implicitly raise questions posed by the American Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife’s takeover of the island: who will be responsible for cleaning up polluted waters, for the people made ill by contamination, and what will Vieques be used for next?

As expansive as the sea is the sky that Helen Mirra takes as the subject for her work Sky-wreck (2001), translated into triangles of indigo cotton sewn together and laid out on the ground. In this representation of something as intangible as the sky, she was inspired by the geodesic designs of architect, engineer and cartographer Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). Mirra’s unfolded fragment of the sky consists of similarly shaped parts, which appear interchangeable and suggest a non-hierarchical order. Originally Mirra made 1/11th of the sky for the Renaissance Society in Chicago and designed the work to break into smaller parts, which refer to their earlier location in the larger work: Northwestern 1 %, Eastern Northern _%, etc. Her structural composition and poetic title (taken from a poem by Paul Celan) confront viewers with a shipwrecked sky that lies beached at their feet. An indefinable place temporarily made tangible.

Geometry and poetry also meet in the work of Gego (Hamburg, 1912-Caracas, 1994), in which a rational and an intuitive order continuously interact. Her drawings and sculptures, that seem to extend endlessly into space, create a place which appears to be ruled by a different time and order. Gego’s work is influenced by her emigration to Venezuela from Nazi Germany in 1939; it centres on investigating the complex influences and relationships between Latin America and Europe. She consciously remained on the sidelines of the geometrical-abstract movement of the 1950s, deploring its focus on assimilation of the scientific and technological aspects of European Modernism rather than on the contrasting world and reality of contemporary Venezuela. Gego found a way of linking her constructivist European training to the Venezuelan context of her surroundings. Her geometric forms always retain an organic element, and her abstraction has nothing to do with belief in a single fixed order. The transparency with which she endows her sculptures make their perception dependent on the position of the observer.

Mauricio Lupini’s Diorama literally confronts viewers head on with the way in which others are represented. He has made a three-dimensional curtain of long strips of paper, cut out of 1978 issues of National Geographic. As viewers pass through it, they encounter fragments of photos and texts about other cultures and places. At the same time the work refers to a geometric, abstract, three-dimensional work created in the 1960s by the Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto, through which viewers could also walk. Soto was the icon of ‘international style’ Latin American art of the 1960s and 1970s. In fact, Lupini re-presents this modern work of art from an ethnographic perspective.

Pablo Leûn de la Barra will run a ‘Parangole’ workshop in which he will make Hèlio Oiticica-style Parangoles with the participants – items loosely resembling coats, jackets and capes (though hardly identifiable as clothing) made of plastic and other scraps of material, and devised with the intention of creating new perceptions. The products of the workshop will be put at the disposal of every visitor who wishes to view the exhibition wearing these garments, thus placing Oiticica’s ‘direct life-experience element’ in the foreground.

Roos Gortzak