N° 82 Army of Me

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

N° 82 Army of Me

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

18 September - 24 October 2004

An artist's studio is a kind of self-portrait. It reflects to some degree the views and personality of the person who works in it. This is how visitors experience it, consciously or unconsciously, including virtual visitors, for photography had scarcely been invented before photographs of studios started to appear and since the emergence of film, television and video it has become increasingly commonplace to grant the public a view of the workplace.

I've always been fascinated by the images artists choose to have around them. They can be highly revealing. Quite fortuitously I open the catalogue of Robert Ryman's 1993 retrospective exhibition in London and see shots taken in 1992 of his New York studio, a bare, very long and lofty space, almost as big as a factory shed. Affixed with drawing pins to part of the long, white working wall are several hundred photographs, arranged in a block. They are black-and-white photos of Ryman's white paintings. On another page of the catalogue is an older photo portrait of the artist by Hans Namuth. Ryman is seated at a trestle table, on the wall above is another block of photos of his paintings, some of the same photos in a different order.

I visit, somewhat less fortuitously, the studio of Eylem Aladogan at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. The floor of the tall, not especially large space, is taken up with crates and boxes of materials; pieces of the complex work she is preparing for her exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam are shrouded in plastic. On one wall are a couple of big, detailed drawings and small preliminary studies. The wall opposite is hung with noticeboards, studded with colour copies of pictures of a very varied nature and origin. A few are reproductions of artworks, classic Chinese pen and ink drawings of mountain landscapes; most are photos, also of landscapes and of aircraft carriers, fighter jets and arms depots, of space equipment and laboratories.

In terms of artistic view and working method, the difference manifested here is one of night and day. For an artist like Ryman the studio is a hermetic domain, closed off from the outside world. Apparently when he is working all he wants to see around him are his previous paintings. It is as if each new painting arises solely from the contemplation of his own work (by comparison Mondrian, of whom the same is said, was a paragon of openness to impressions from observed reality, witness his paintings and the incidental references in the titles to music, dance, and to squares and streets in Paris, London and New York). An artist like Aladogan, by contrast, admits the whole world into her studio. It is a receiving station for all sorts of information that form the seedbed from which her work grows.

Unlike many of her colleagues, however, there is no question or even suggestion with Aladogan of the reproduction of reality. Her work is not realistic, not documentary or pseudo-documentary - these days an all-powerful trend that generally finds expression in the excessive use of photographic and cinematographic devices. The characterization that springs most readily to mind, however anachronistic it may sound, is 'symbolistic', but in the original meaning of the word. Late nineteenth-century symbolism was not, as is often supposed, about clear-cut symbols, but about atmosphere, suggestion, representation. The same holds true for Aladogan's work. Typically, the information she gathers from reality, in the form of pictures and otherwise, undergoes a metamorphosis, is transmuted or merges to form a new whole and so become receptive to new meaning.

This metamorphosis is given very concrete form at the material level. Aladogan's art undoubtedly involves a lot of thinking; all kinds of possibilities are considered and either rejected or developed further, but the crucial thing is the execution. Here traditional craft techniques, like the working of clay, engage with a sophisticated use of modern technology. This was already the case in earlier installations, beginning with Birds, a work she exhibited in 1999 in the final year show of the Rotterdam academy of arts and thereafter in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen and in Galerie Fons Welters. Laid out on a pathologist's table were several large birds, modelled very delicately and in great detail from grey unfired clay, kept moist by clouds of water droplets dispersed by a sprinkler system. The birds appeared to have met their end as victims of some ecological disaster in shallow river flats where the clay was bleeding tendrils of colour and would eventually, at an almost imperceptibly slow pace, dissolve in the water. At the same time the table and the sprinkler system undermined the suggestion of a natural habitat, turning it in an artificial direction.

The interlocking of nature and technology was even more trenchantly rendered in the installation 'Pharmagenic Decline (you won't suffer any harm)' that Aladogan created in Museum Het Domein in Sittard in 2002. There, arranged on two curved, white tiled platforms in a clinical-looking space flooded with bright white light, were eight sculptures of fired clay glazed in a muddy, brownish-green; at first sight somewhat indeterminate forms until, with a shock, the viewer recognizes them as the remains of animals: here and there a leg, a snout protrudes from the inert mass; trails of clay can be read as strips of hide or strands of wool from a sheep, tubular bits suggest ribs and bones that have been exposed. Sprouting from the false ceiling above this tableau of animals that appear to have fallen prey to other animals or to human beings, are shiny metal rods that end in the kind of shears used on sheep. Like long grab arms they grope towards the clay shapes but they do not move; it is a dramatic moment frozen for eternity.

Aladogan is obviously fascinated by biology, genetics, ecology and other scientific fields that are concerned with the organic world and that play a vital role in today's society. Such interests are not unique in contemporary art, but while other artists sometimes go quite far in adapting scientific practices (classifying, constructing systems, conducting experiments) and again tend to be realistic in what they do, for Aladogan the scientific textual and visual material seems to function chiefly as a stimulus for the imagination. She appropriates it and transforms it into situations that have something personal and mysterious about them. They do not allow themselves to be pinned down to a particular interpretation; they are evocative, appealing to the viewers' emotions, to their fears and dreams and sense of vulnerability. In effect, cold technology and objective science are deployed for the sake of subjective perception.

With the ambitious 'Army of Me' installation devised for Bureau Amsterdam, Aladogan has turned her attention to new areas. An indication of this are the afore-mentioned images on the wall of her studio. The starting point is modern warfare as currently being waged for example in the Middle East, or at least the image we get of this human, all too human activity, via the press and television. It is an image fraught with contradictions and alienating effects. On the one hand, as newspaper readers and particularly as television viewers, we are spared nothing of the horrors and violence: executions, attacks with civilian casualties, bombardments that raze entire districts to the ground. On the other hand, we occasionally see photos and television recordings that involuntarily conjure up a dream world rather than reality: artillery fire above Bagdad like fireworks on a national holiday, shadowy tanks ploughing through a sandstorm like prehistoric animals, the streamlined shapes of missiles stored in a depot. And we see photos of the command centres from where the war is controlled and conducted, immaculate spaces reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick's '2001 - A Space Odyssey' equipped with monitors that reduce the whole conduct of the war to a game of Stratego with abstract symbols.

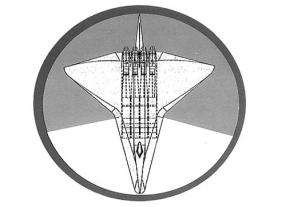

It is this paradox that is explored in 'Army of Me' and personalized - the title refers to this. The work is a three-dimensional collage containing elements that evoke different atmospheres and locations. On a stand in the middle of the main gallery is a large replica of the B-2 Stealth bomber, a fighter jet invisible to radar. A landing strip has been indicated on the floor. Part of the space has been partitioned off and turned into a display room for a number of flags bearing the emblems of a fictional army. In another corner there is the suggestion of an aerial view of bare rock formations like the mountains on the moon or of vertiginously deep canyons. In the small rear gallery a 'fallen' glass star rests on a bed of parachute silk.

The objects are recognizable; about their origins and the context in which they normally function there can be no uncertainty. Nonetheless, the installation belongs unmistakably to the realm of the imagination which we enter with curiosity, attracted by the bright light. There is something seductive and bewitching about the shiny material of the regimental flags, the glazed mountains, the clear glass of the star, the mother-of-pearl surface of the bomber, and at the same time something distressing and oppressive, because it is a dangerous beauty that Aladogan presents to us in 'Army of Me'.

Carel Blotkamp