Wunderland Unframed

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

Wunderland Unframed

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

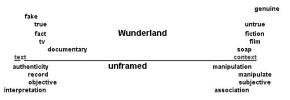

17 July - 29 August 2004

Guest curator: Andrea Wiarda

In Wunderland unframed, the ad hoc Flemish collective of Anouk de Clercq, Joris Cool and Eavesdropper, and Dutch artist Govinda Mens cast an eye over the marvellous mental landscape of understanding, memory and imagination. In a more tightly focused contribution, Barbara Visser evokes the visual exhibition history of Bureau Amsterdam. Wunderland is the landscape of images framed by the concepts presented at the top of this article - the visual Babylon of 24-hour television, live news, reality TV, soaps, commercials, films, newspapers, magazines and Internet. Wunderland is also the marvellous mental space in which the images we see every day are stored. As in Alice’s Wonderland, the relationships, possibilities and meanings are different from those of reality. The landscape of our imagination cannot be taken in at a glance; time and again a new perspective presents itself, a situation is created or an image or a new outlook (or insight) is conjured up. The artists involved in Wunderland unframed explore issues relating to the credibility of images, the way images acquire meaning or are furnished with a context in terms of space, location, manner of presentation, but also in the media - on television, in news programmes, newspapers and magazines and the world wide web. The exhibition takes as given the relative incredibility of images; the subjectivity of interpretation and the way it depends on context, ‘observer’, experience, knowledge, belief... Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak. But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.1 How do we know what we see? John Berger backed up the statement quoted above with that classic example of the representation of perception, Magritte’s The Key to Dreams (‘English’ canvas from the La Clef des Songes series, 1935). It depicts four pictures and four words on a school blackboard; below the picture of a horse’s head are the words ‘the door’; the drawing of a clock is labelled ‘the wind’; the picture of a jug is captioned ‘the bird’ while the final picture, of a suitcase, is labelled ‘the valise’. The blackboard contains eight items, each of which refers to something that exists in reality. The confusion we feel when looking at this painting is only partly due to the mismatched words and images; the French-speaking artist also uses English words complete with definite article (which school alphabets never do) and the final word-image pair is correct (apart from the article) but in a different language. All these things combine to confound the observer’s prior knowledge and assumptions (expectations).2

U n f r a m e d

Such spatial associations are reminiscent of more contemporary ‘collections’ of images and information: the world wide web, digital databases, television (that cabinet of curiosities in the living room), the visual world conceived as a sort of cabinet of hyperlinks. Could we perhaps see our memory as a cabinet of hyperlinks in which images, sound, text, space/context, medium and so one inform one another? Much is possible in art; art can cast a creative and critical eye over images, over the conventions, media and mechanisms of the image culture and over the communicative and manipulative nature of images. Contemporary image makers can play with those visual and communicative conventions; attempt to generate an image with visual elements; ponder what it is that generates an image, or what an image consists of, and what happens to an image; they can break through the frame of the visual image. It seems only logical that the roles of artist and observer should overlap one another (in practice as well as theory): the artist is also an observer and observers create their own meanings and associations, their own relation/link with the proffered ‘image’.

Although the exhibition is about images in the context of the visual arts, no ‘traditional’ framed images are shown. Instead, a complex combination of elements forms the basis for a still ‘image’ that in turn raises questions about that complexity of looking and of making images. Visual conventions are abandoned and images are generated by new technologies, imagination, sound, text and memories. Images are deliberately taken out of the specific framework of visual art and shown anew, or simply suggested, undressed... unframed.

Rather than taking signification or even mass media implication as the subject of their work, the artists involved in Wunderland unframed, the Flemish collective of Anouk de Clercq, Joris Cool & Eavesdropper, Govinda Mens (NL) and Barbara Visser (NL), deal conscientiously with the creation of images, of ‘viewing situations’. Their interest is in the power of representation, in the possibility of repeatedly creating new ‘images’, ‘forms’ ... and meanings, of ‘giving reality’. These artists do not want to convey a message (to classify) but to suggest and approach alternatives; to investigate the structures and mechanisms that underlie the viewing and understanding of images. All the artistic aspects - the creative process, choice of media, the presentation/context and above all the observer - play an important role in this.

The video works of Anouk de Clercq, who studied music and film in Vlaanderen, are often developed in collaboration with professionals from other artistic fields on the basis of her own general concept. Joris Cool, who studied architecture and animation in Brussels, is a regular collaborator, but she also works on and off with musicians, choreographers, fashion designers, new media specialists and so on. It is this kind of collaboration that gives added depth to her work and enables her to create and manipulate images using the latest computer and 3D software, music and graphic elements and in so doing to allow scope for improvisation and chance.

In Wunderland unframed, Anouk de Clercq presents a new work devised in collaboration with Joris Cool and Eavesdropper. It is a digital projection, a ‘sonic landscape’, that operates on the border between the visual and the auditory, the abstract and the figurative, the spontaneous and the programmed. It is a tale told in computer images, a combination of animation and music. It is a futuristic dreamscape that stimulates the imagination and offers a ‘new reality’ without allowing the technological implications to overshadow the narrative aspect and the representation.

The title of the Flemish collective’s work, Kernwasser Wunderland, was inspired by an advertisement for the ‘nuclear reactor’ amusement park of that name (near Kalkar in Germany) and images of the desolate environs of Chernobyl. The uneasy conflation of nuclear disaster and amusement park is elaborated in an (abstract and futuristic) landscape - intense and silent, hovering between eerie and idyllic, between fact and fiction - accompanied by an electronic soundtrack that musician Yves de Mey aka Eavesdropper composed image by image.

Anouk de Clercq and Joris Cool exploit the possibilities of digital technology to the utmost in their quest to explore and extend the limits of an image or a sound. De Clercq, Cool and Eavesdropper make no distinction between image and sound: the keen dynamic they establish between digitally generated abstract sounds and graphic images is intended to enable the viewer to ‘listen to pictures’ and ‘look at music’. Viewers either follow the intuitive logic of this representation or introduce their own pictures into the landscape which becomes a kind of ‘memory-scape’.

Anouk de Clercq and Joris Cool’s Kernwasser Wunderland ‘image’ acquires an almost immaterial context as a result of the interventions of the Dutch artist Govinda Mens. Mens makes spatial works, which is to say works that encompass the space in which they are presented. The exhibition space is organized and manipulated so as to offer viewers a particular experience. Like De Clercq, Mens takes a keen interest in developments in other disciplines and has even worked within the framework of the theatrical and musical disciplines. In 2002 she collaborated with Victoria and the Need Company in Belgium and more recently she worked intensively with theatre professionals, composers and Orkest de Volharding to produce Soirées Unextracted. In addition, she developed the concept and spaces for ‘muZIEum’, an experiential museum in a library for the blind in Nijmegen.

Latterly she has also started to explore the manipulative effect of visual material from the mass media. She believes that the choice of medium plays a major role in the way images are interpreted and ‘believed’, as does the interaction between image and text - the impact of headlines on newspaper photographs and vice versa. For Wunderland unframed, Govinda Mens has made a number of changes to the front and rear spaces of Bureau Amsterdam. Her interventions, which concern the simultaneous presence and absence of the image, provide both a prelude and context for Kernwasser Wunderland.

Barbara Visser is similarly interested in the power of representation and in particular the distorting effects of memory. The relation between reality and fiction, real and manipulated, original and copy, half and whole truth, is a recurrent theme in Visser’s work. As part of SMBA’s tenth anniversary in 2004 she presents a (re)interpretation of Bureau Amsterdam’s exhibition history in which the roles of artist and observer, of maker, narrator and viewer, become blurred. Visser asked Jan ‘who saw it all’ Meijer, who has worked at SMBA since its inception, for his visual recollections of ten years’ SMBA. Visser approached this visual memory as a biased archive - as all archives are in fact ‘biased’ by the selection and ordering of the data. The observer (Meijer) describes the work of the ‘makers’ (the artists who exhibited in SMBA) based on his own memories (and imagination) to another maker (Visser) who is (and was) herself an observer of that same exhibition history and who then proceeds to turn that memory into an artwork. Those memories are not processed and generalized in a purely visual manner but in the form of text. The actual visual history of Bureau Amsterdam is examined and represented as a subjective history. The record of Meijer’s memories constitutes one more individual account of ten years’ SMBA; for some it will strike a familiar note, for others it may serve to trigger the imagination.

Andrea Wiarda