The Power of Partnership

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

The Power of Partnership

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

8 September - 20 October 2002

There is a deep-rooted desire in our culture and an overpowering sense of purpose for the search of happiness. It is promised by politicians, sold in holiday brochures, or sung about in every mediocre hit. The idea is simple: if we can create a contemporary society in which individuals are able to develop, then happiness must surely lie within everyone’s grasp. Or does it?

The refutation of this rhetorical question forms the leitmotif in the work of the artist Tim Stoner (London, 1970). Stoner works in the medium of paint, which is not an obvious choice, since the worn out, nonsensical question of whether painting is relevant pervades and corrupts looking itself. Yet through the development of a transparent, apparently clear personal language, the artist manages to rid himself of this ballast.

Without exception, light plays a major part in Tim Stoner's paintings, delineating the glow of an atomic flash, a divine ray, or the ever-present, but never truly visible sun. These intangible landscapes are staffed by figures which, willingly or not, are all connected. In earlier works these were aspiring couples who, hand-in-hand, walked towards eternity together. More recently, groups of companions appear in paintings that show a bygone age or invented traditions such as folk dancing, initiation rituals, or social rites.

At first glance, Tim Stoner's, usually large canvases, appear to be a reflection on the contemporary void; the suburbs, or the peripheries of the big city, which set the scene for these anonymous silhouettes. The seemingly supreme state of (superficial) happiness in which they think they find themselves, is brushed away in a multiplicity of virtuoso strokes. The peintre fatale seduces under false pretences: the paintings appear treacherously beautiful and safe, but the pleasure soon turns to unease.

Through a deliberate lack of texture the works posses a surprising naturalness; although concerned with painterly process, there is a gestural mystery to their layers, as if they had simply always been there. The iconography shows the nuclear family filing past, or the uneasy little dance of bored townspeople imitating the rural life of times gone by; individuals becoming entangled in a self-invented ritual. What is intended to pass as an evocation of a lost world degenerates into an unintentional parody of the past.

The two works Feste and Patriots show the type of traditional scenes in which middle class tourists seek to find their roots. This longing for originality is mercilessly dissected, particularly in Feste where we see the premeditated transformation of a supposedly authentic dance into kitsch. More than other works, Feste reveals how Stoner builds up the paint, layer upon layer, as if super-imposing one shadow over another. The transparency of these films of paint allow the colour to remain exceptionally visible in places, while still appearing to merge, creating a trompe l'œil of colour and depth, a sort of three- dimensional shadow play. In Patriots it is the flashy pose held in a traditional costume, which unmasks the work. However, what makes both works sublime is that the painter does not explicitly adopt an ethical position, but leaves interpretation open to the eye of the beholder. What you want to see is not necessarily what you see.

The enigmatic work Smoke is of an entirely different order. It is unclear as to whether the couple represented here is surrounded by cigarette smoke or some kind of haze of energy. The clouds of smoke bind the couple, holding them in a transient, but compelling grasp. As with many of Stoner's paintings, there lingers a kind of retro- futuristic atmosphere: the painting appears contemporary, while also exuding a claustrophobic and nostalgic air.

The painting Eton makes perhaps the most political statement. This famous English public school is an institution which continues to symbolize the English class system. With this theme and the way it has been made, the work attempts to embody and comprehend the idea of institutional class. The painting shows two boys wearing the school’s festive flowery hats. However, the backlight makes it look as if the natural forms have been redefined, their brains appearing to flow out of their overfed heads. Instead of this being a cerebral burden, the boys wear the inflated intelligence like crowns similar to the one worn by the school’s weak and corrupt founder Henry VI. In a single image Stoner manages to subtly, yet clearly expose the foundations of English society with its lack of emotion and its hankering after the tradition of a deeply embedded class system.

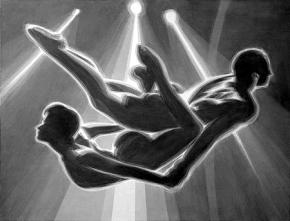

Significantly, yet not accidentally, Stoner's latest works were made in Malaga, London, Amsterdam and Rome. The cosmopolitan aspect of the works is implicitly reflected in the European pictorial styles he has used to translate the images. Stoner painted Void, saturated and vibrating with light, after having studied Bernini's Saint Theresa in Ecstasy, while Union, with its references to medieval symbolism, may clearly be placed within a Northern European context.

In terms of form and content, these two paintings seem to be each other's opposites in more ways than one. Void is the only work in which Stoner reveals his light source, whereas in Union, as in other works, it remains invisible, though no less important. Furthermore, the protagonists in Union appear to be linked through nothing more than a few bizarre totems of animals, a lost angel and even an upside-down monarch on his throne. This connection is essentially purely fetishistic.

Conversely, in Void, the almost acrobatic entanglement of the two bodies is not just physically tangible; it is above all a matter of survival and without mutual trust they will enter into free fall. Or is this also simply a matter of appearances? Will this elegant, decoratively floating couple remain doomed to be trapped, condemned to each other, for all eternity? It is not without reason that title of the painting refers to the second verse of the Old Testament: 'In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void'. But unlike biblical paintings, which literally depict how Adam and Eve were driven from the earthly paradise, here it is the intertwined limbs in a sea of light that evoke an illusion of eternal attachment. Only one thing has to go wrong in this precarious equilibrium for the figures to vanish forever, consumed by the dark void.

Jos Van Den Bergh

Translation Annabel Howland