Bunta Garbo

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

Bunta Garbo

Please note: Flash 7 or higher is required to properly view this website.

Click here to download and install the latest version of Flash

12 May - 23 June 2002

Although Democratic Governance has been seen to have been superseded by the power of globalised industry, the elected ‘leaders’ of the world’s seven largest national economies assembled in Köln’s Museum Ludwig in June 1999 to discuss the world’s economic situation together with Boris Yeltsin beneath paintings by Morris Louis and Mark Rothko.

The environment in which they sat was commissioned by the German Federal Foreign Office from the artist Matti Braun. An accompanying press release described Braun’s centrepiece: ‘The central feature is the round table with a diameter of 3.50m. The table’s surface and the column in the middle form one large indivisible unit. The whole table is made from pearl-white polyester fiberglass: the working surface is laid with a grey circle of linoleum. The center is marked by a green dot’. Loosely encoded within this description is a summary of the generic formula for progressive 1960’s furniture - moulded in one piece from polyester fibreglass and pared of sharp edges. This is the type of furniture that was supposed to accompany the anticipated Leisure Age. Braun’s table symbolically erupts from the floor like a three dimensional approximation of a Kenneth Noland painting.

The Conference organisers chose the Museum as it afforded a position of security from another international collection of different ideas and interests - those of protestors. Braun’s photographic documentation bypasses the Museum’s security systems to expose the assembled dignitaries, their translators and guards all of whom were unaware that their carefully orchestrated surroundings articulated their outdated assembly and anticipated their inevitable failure to make any real difference to anything.

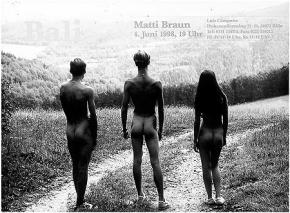

Braun’s commissioned conference suite for the G8 summit sits amongst several works that engage with an eclectic catalogue of incongruous projects from our recent cultural history; projects that challenge orthodox understandings. In ‘Bali’ (1998) Braun referred to the artists’ community, Pita Maha (or Strong Determination), founded by Walter Spies and Walter Bonnet in Ubud, Bali during the late 1930’s. These artists from Germany and the Netherlands introduced tempera and watercolour and in turn appropriated local themes and mythology into their own work under the local patronage of Cokorda Gede Agung Sukawati. Before his premature death in 1942, Spies also co-choreographed a number of ‘traditional’ Balinese dances which are still performed to Western tourists today.

Braun’s ‘Edo’ (1999) makes reference to Yorozu Tetsugoro (1885 - 1927) a founder member of the Fyuzankai group of Japanese painters. Tetsugoro is credited with producing the first Modern, non-representational painting in Japan - an untitled work from 1912. However, abstraction had been long recognised in Japan - a country where Western ideas of perspective had been considered at first to be a gimmick. Western abstraction had also of course been inspired directly by Japanese tradition.

‘Ghor’ (2000) refers to Leopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001) an acclaimed poet and President of Senegal. Senghor was the first African member of the Académie Française and yet was also a promoter of Négritude. During the 1970’s Senghor famously commissioned a bust of himself and a proposal for a Monument of African Liberation from Arno Breker, the chief sculptor of the German Third Reich.

Braun’s project for the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, ‘Bunta Garbo’, excavates the little known work of the Belgian writer Andreas Juste (1918-1998). Like Senghor, Juste was a devout Catholic from a cultural crossroads, not in Central Africa but Gilly, in the suburbs of Charleroi, Belgium where he worked as a lawyer. Written in the ‘international language’ Ido, Juste’s entire literary output (of approximately twenty five self-published novels, collections of poems, pamphlets and translations) is largely unavailable and were it be so, could only be properly understood by probably, at most, 1000 readers world-wide.

Depending upon who you consult Ido is either a corruption or refinement of the best known ‘international language’ Esperanto. ‘Lingvo Internacia’, or ‘International Language’ was published as a Russian textbook in 1887 by Ludovic Lazar Zamenhof in Warsaw, then part of the Russian Empire. Writing under the pseudonym ‘Esperanto’, or ‘a person who is hoping’ in the language that it described, Zamenhoff attempted to condense the estimated 2,500 languages of the world into one that could be universally applied as an auxiliary language or bridge between different speaking peoples.

Zamenhoff, a Polish Jew, grew up in Bialystok in Russian occupied Western Poland within a multilingual community of Jews, Poles, Russians, Lithuanians and Germans. The search to identify a unifying auxiliary language held obvious appeal. Zamenhoff was not the first person to single-handedly construct a language. The first known is the ‘Lingua Ignota’ that was pioneered by a 12th Century Abbess of Rupertsberg, Hildegarde of Bingen. Given that 12th Century European societies had an existing common language in Latin, her pursuit cannot be seen as one that would advance communication but instead as a Gnostic code. Zamenhoff should be seen instead to have been working within a tradition advanced in the 18th Century by the likes of René Descartes, in France, and Jan Amos Comensky, in Czechoslovakia, that sought to replace Latin, the language of the reactionary Catholic Church, with a language that would unite rather than to divide. Zamenhoff simplified existing complex grammatical rules to create a regular and exception free means of language construction. He also devised a similarly regulated and phonetic spelling system. Zamenhoff’s ‘Lingvo Internacia’ or Esperanto, as it became known, was built from around five hundred key words derived from the vocabularies concealed within the existent European dictionaries in such a way that it was easily adaptable so that new words could be created when necessary.

By 1900 representatives from the rapidly growing number of diverse international language speaking peoples met together with Zamenhoff at the Universal Exposition in Paris to decide upon the course of diverse lingue franche. It was determined that a ‘Delegation for the Adoption of an International Auxiliary Language’ be formed. In 1907 a committee was created to explore the Delegation’s findings. After a further eighteen meetings, the Committee, consisting of, amongst others, Professors Otto Jesperson (a linguist), Richard Lorenz (a physicist) and Wilhelm Ostwald (a Nobel Prize winning chemist) and Louis Couturat (a mathematician and philosopher) and Louis de Beaufront (the leading advocate of the Esperanto movement in France) announced their findings at the College de France in Paris. They proposed the adoption of a reformed version of Esperanto. Proposed reforms included abandoning the accented letters that had obstructed print production (as commercial printers were reluctant to invest in the necessary new letterpress components), the establishment of a vocabulary with neutral gender and the removal of Esperanto’s agglutinative morphology and of any of its Slavic syntax. These findings resulted in the creation of ‘Esperanto Reformita’ or, as it came to known, ‘Ido’ - a Esperanto suffix meaning ‘descended from’. Reform of the naissant language would inevitably cause a rupture as ‘to improve’ inevitably, also means ‘to purge’ and on the eve of the 1914-18 War the ‘people that were hoping’ split into two ‘Bunta Garbo’ presents a series of proposals for the covers of reprinted editions of the works of the best known Idoist writer - Andreas Juste. Just as Ido draws from a broad source of existing language, Braun’s proposals adopt a wide array of imagery to illustrate the works of Juste. These designs are accompanied by a series of web-like structures that perhaps articulate the way in which idealistic universal movements inevitably take form - as a series of fractious cells. And yet in Braun’s structures these cells are seen to interconnect rather than exist in isolation from one another.

International language speakers can be seen to congregate into a series of minority groups with otherwise contradictory ideas to one another. High profile exponents of Ido have historically included political dissidents from both the left and the right and have accordingly been persecuted by authoritarian regimes. Amongst Ido users today are readers of the Gay and Lesbian magazine La Kordiego Geyal and simultaneously, followers of the Catholic Church, which fundamentally opposes homosexuality. At the same time Ido has become a language of disaffected youth through its adoption by discordant rock bands with the advent of so called ‘Esperantocore’ and by Buddhists who in many ways can be seen as cultural opposites. Perhaps Ido can be seen to find a role as an international language of marginalised peoples rather than as a tool of Eurocentric Imperialism (being in some ways the by-product of a colonial Universal Exposition). ‘Bunta Garbo’ asks how users of auxiliary language can come together in international conference with a shared understanding of, and a passion for, the eclectic writings of Andreas Juste.

Just as Juste's writings form an oblique locus - an obscure point of intersection between different ways of thinking - so Braun's installations, with their fractious structures, reflective surfaces and moulded furniture, are similarly complex. Braun's works do not offer explanations to the histories that inform them but offer instead a series of loci that articulate that there are no explanations, no simple trajectories between ideas and actions. Whether informed by international assemblies, or the minds of individuals trying to find a consistent position, Braun's works articulate the seemingly endless plurality of cultural traditions and vocabularies.

Rob Tufnell, 2002

Assistant Curator Dundee Contemporary Arts

1. Morris Louis¹ Alpha-Ro and Pillar of Dawn (both works 1961) and Mark Rothko¹s Earth and Green (1955)

2. One of which is to be taken beyond prototype and adopted by the Amsterdam publisher Tia Libro taking Braun¹s project beyond the gallery context and into the Ido subculture.

3. In 1928 the World League for Sexual Reform adopted Esperanto as its official language at its inaugural conference in Copenhagen

.4. Pichismo, the Ukrainian punk band and self proclaimed founders of Esperantocore have set poetry by Andreas Juste to music.